The Cahokians were Doomed by a Changing Climate. Are We?

Those who don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it.

Ironically, we’ve been repeating and simultaneously ignoring this famous adage for centuries. And it might just be our downfall.

Right now, the world is split between climate-deniers and climate-activists. Some petition for a cleaner world and greener legislation while others laugh in their faces. Yet, no matter one’s position on climate change, one thing is clear: a changing environment could be our downfall.

And if you don’t believe it, just look to the past.

The Cahokians

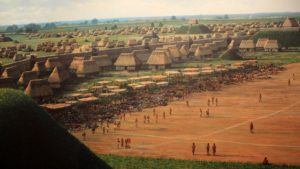

The Cahokians were a Native American tribe that lived in modern-day Illinois from 700 AD – 1200 AD, far before Columbus reached America. This tribe differs from other, more well-known Native American tribes because the City of Cahokia is considered one of the most advanced settlements in ancient America.

Cahokia consisted of wooden and mud homes; borders to protect the city; an astronomical “Woodhenge” similar to England’s Stonehenge; a thriving economy based on trade with various other tribes; an abnormally large population; and successful agriculture practices. The Cahokians even erected large mounds on which the rulers’ homes were built in order to look down on the people of Cahokia.

According to archaeologists, Cahokia did well in regard to food security. During this period in time–the Medieval Climatic Anomaly–the weather was unusually warm and there was plentiful rain. This, combined with the fact that Illinois’ soil was incredibly fertile and easy to till, meant that farming was relatively easy. Corn was a major staple in the Cahokian diet–and according to archaeological research, there was a lot of it. The Cahokians also grew goosefoot, amaranth, and other crops.

They were doing well for themselves. Until the climate began to change.

The Fall of the Cahokians

Around 1200, the weather began to shift.

Due in part to increased volcanic activity, the warming period that made life so easy for the Cahokians began to reverse. It got colder, and in 1150, the Mississippi River flooded dramatically.

Then, in 1350, a profound drought hit. A jet-stream shot cold air from thee arctic into North America, lowering temperatures while cultivating a drier climate. This period in time, dubbed the Little Ice Age, didn’t end until 500 years later.

And it wasn’t just colder, drier weather or flooding that did these people in. Archaeologists have suggested that poor agricultural practices and deforestation played a role in their demise. In Illinois, small increases in water levels can destroy farmland, so flooding could have made agriculture impossible. In addition, deforestation of the trees along nearby bluffs caused soil erosion, which made cropland too marshy to grow corn, their main staple.

Archaeologists don’t truly know what happened to the Cahokians. The City of Cahokia was long abandoned before Columbus set foot in America. In fact, many of the Mississippian tribes who conversed with European explorers had no idea who inhabited the City of Cahokia.

Some speculate that political tensions led to war. Others speculate that the changing climate led the Cahokians to seek better land. Whether or not a tremendous flood or bitter cold wiped out these native peoples is irrelevant. What archaeologists can agree on is that the changing climate made these people more vulnerable.

Climate Change Breeds Vulnerability

The Cahokians were vulnerable to begin with.

The borders that protected their city had been torn down and rebuilt various times, suggesting that others had tried to invade their land. The City of Cahokia was a bustling trade center; natives from as far as Oklahoma and the Carolinas sought to trade with the Cahokians. These were advanced peoples with intelligent minds, sophisticated astronomical technology, and valuable land. Others surely wanted what they had.

Political tensions within the city also made these people vulnerable. Mississippian tribes that employed similar societal ranking structures as the Cahokians (in which one’s blood determines his or her worth) failed miserably at this time in history. None of them lasted longer than 150 years.

A changing climate, failing crops, and hungry people are all variables in an equation that leads to a messy end. When people are hungry, cold, and frightened, tensions begin to rise. Tension stemming from class structure and invading forces would have added to this, breeding a tribe of people vulnerable to extinction.

And, uncannily, the U.S. is facing a similar problem.

A Vulnerable Country

Most of the United States’ people are not starving. In a lot of places, where food deserts prevent access to affordable and healthy food, people are food insecure. People who face poverty are also food insecure. But, no, the U.S. as a whole is not facing some sort of food crisis.

But we could–very soon.

The world grows 95 percent of its food in the earth’s topsoil, which is the uppermost layer of soil. Yet, in the last 150 years, half of this topsoil has disappeared. And according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, we will lose all of it in 60 years.

Reread that.

In 60 years, we will have run out of topsoil. The soil we need to grow crops.

You might be thinking: wait, it took 150 years to run out of half of it. How can we only have 60 years left?

Our soil is actually eroding 10 times faster than it can be replenished. So while it may have taken 150 years to get to this point, it will only take 60 more years for us to reach the bottom of the barrel. And when we do, we won’t have anywhere to turn. Much like the Cahokians, we’ll face various issues and rising tensions: a changing climate, failing crops, hungry people, and political turmoil. Possibly even war.

But, unlike the Cahokians, we won’t have anywhere to turn.

While we seem to be following the footsteps of civilizations past, we don’t have to end up in the same lot. Because many of the environmental issues we face today (whether they were caused by humans or not) can be solved by humans.

Choosing a Different Path

Rather than waiting for the impending storm or fleeing a damaged earth, we can restore the earth to what it once was.

The topsoil on which we rely has been degraded by conventional agriculture practices. This is undeniable. Farmers have relied on unsustainable practices that were developed in order to make large profits and yields in a small amount of time. But that’s just the thing. We knew they were unsustainable (meaning they could not last forever). Now that these methods have run their course, it’s time for farmers to move on to sustainable practices that can help replenish the earth and our people.

The following practices have contributed to the loss of our world’s top soil:

- Excessive Fertilizer Use

- Tillage

- Lack of Cover Crops

- Monoculture

Conventional Agriculture Practices

Fertilizer was invented as a way to help crops grow stronger, bigger, and healthier. It’s a miracle invention that, when used correctly, can dramatically improve crop yield. Unfortunately, we misuse fertilizer on a large scale.

Plants only take up as much as they need, so when they’ve got their fill, they stop absorbing nutrients. Yet, farmers have doused their fields in fertilizer for decades, erroneously believing that more fertilizer would equate to a larger yield. When plants don’t absorb fertilizer, it’s either washed into rivers and streams or consumed by soil microbes and belched into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas). In addition, when fertilizer sits in the soil with nowhere to go, it can destroy soil crumbs, mineral rich deposits that improve soil drainage. So excessive fertilization can also lead to erosion.

Tillage, which entails churning the soil to prepare it for new crops, obliterates top soil. And all the organic matter and litter that once sat in that layer vanishes. Tillage also releases stored carbon from the soil and into the atmosphere. Cover crops help keep carbon in the soil, but many farmers don’t employ them. So, not only is this bad for the environment, but it’s also bad for farmers. For every one percent increase of carbon, an acre of land can hold 40,000 more gallons of water. Tilling the soil, refusing to employ cover crops, and releasing carbon decreases soil’s ability to retain water.

Due to the popularity in soy and corn, farmers have long grown these two crops on their land without switching them out with other crops. This practice, which is called monoculture, is incredibly bad for the soil. Growing one crop over and over again doesn’t give the soil a chance to recover. Furthermore, farmers practicing monoculture won’t use cover crops, so carbon is lost when their crops are harvested and the soil is left bare.

Luckily, we can change our ways and begin repairing the soil with something called regenerative agriculture.

Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agriculture seeks to repair the soil by:

- Using less fertilizer and opting for more natural products

- Eliminating tillage

- Introducing cover crops

- Employing Polyculture

By using less fertilizer, farmers will be able to reduce erosion and pollution. Eliminating tillage will help protect topsoil and reduce carbon loss, which will cut greenhouse gas emissions and reduce erosion. Introducing cover crops will protect the soil from harsh conditions, reduce carbon loss, and replenish the soil, as many cover crops are rich in nitrogen and other minerals. Lastly, by employing polyculture instead of monoculture, farmers can support their soil while reducing crops’ susceptibility to disease.

Looking back on the Cahokians is like staring into our own reflection. But it doesn’t have to be. One ripple of change can alter that reflection and change our civilization for the better.

Sources:

Metropolitan Life on the Mississippi

Climate change contributed to fall of Cahokia

1,000 Years Ago, Corn Made This Society Big. Then, A Changing Climate Destroyed It